|

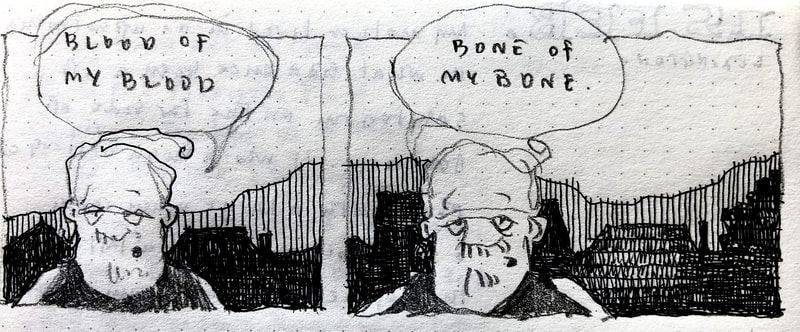

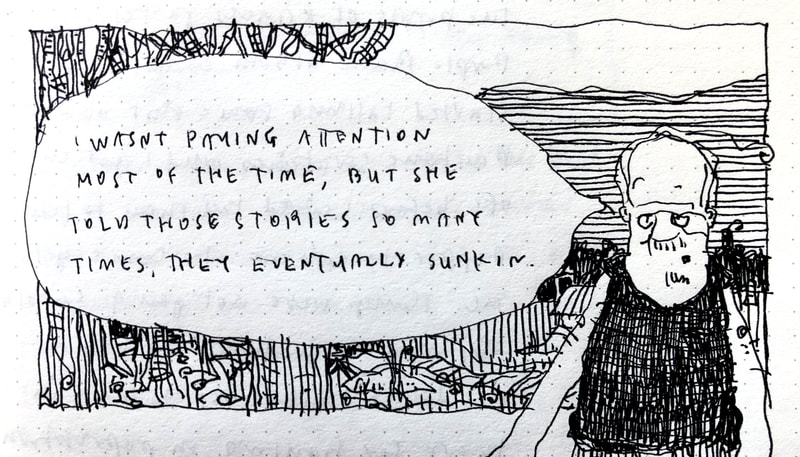

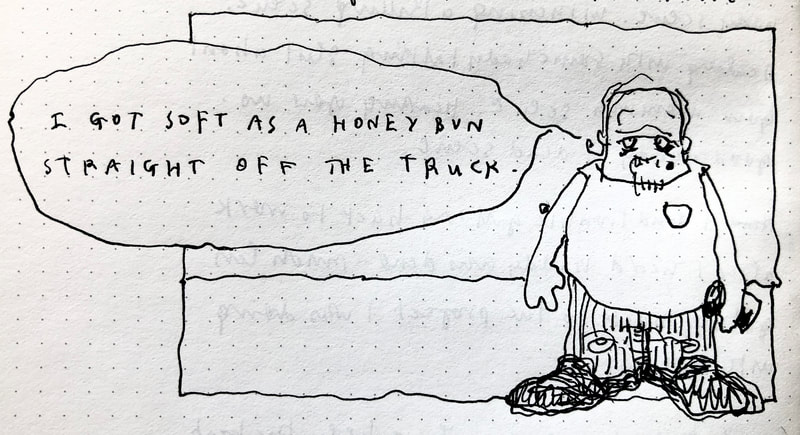

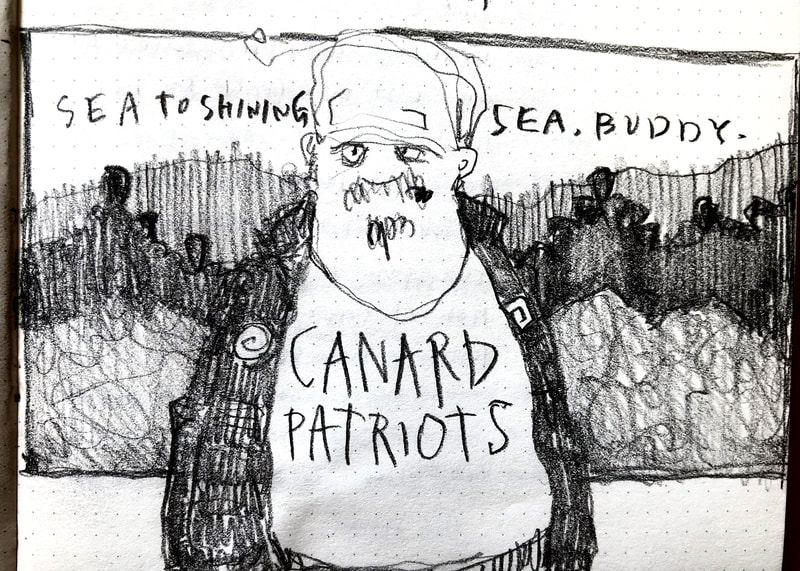

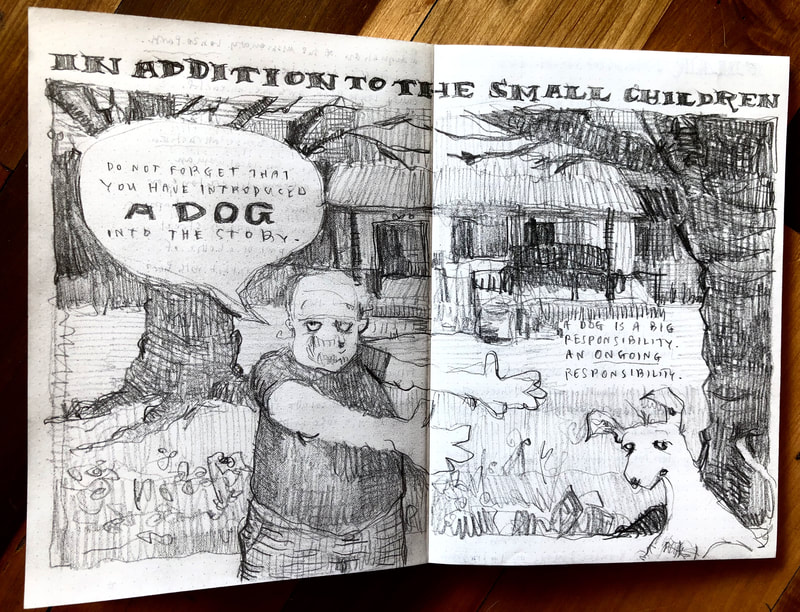

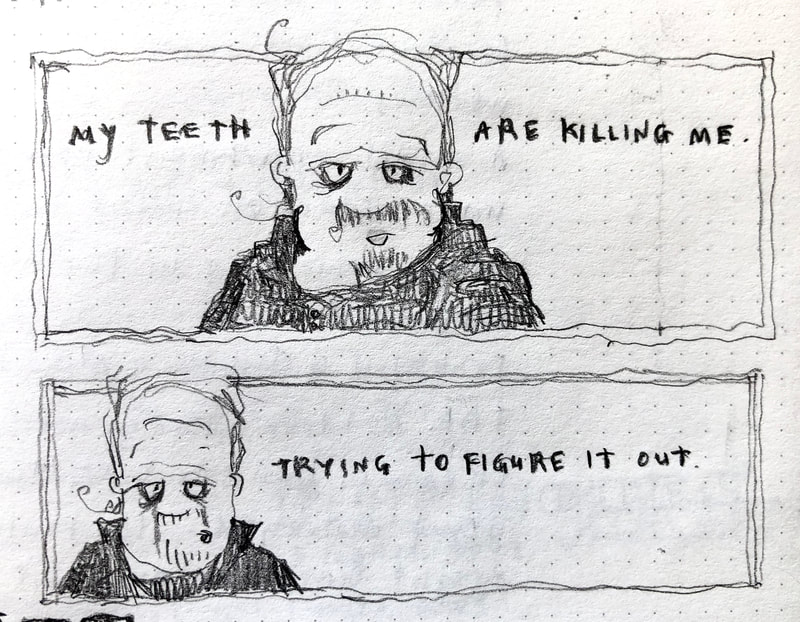

Hubert is in his sixties now. His partner Tildy is dead. He lives on top of Long Ridge. He has grown fogbound and disgusted with himself. Here are some pictures of him I found in my notebooks.

I wrote this for and read it at The Arnow Conference In The Humanities at Somerset Community College in Somerset, Kentucky on April 7, 2022. I appreciate them asking me to do it.

It is a heady time to be in the humanities business. We have never been so relevant nor so close to extinction. The emergence of critical race theory as a wedge issue has turned elections, gotten people fired, threatened lives. The renewed zeal for banning of books discussing gender, race, and sexuality has turned teachers and librarians into some of the most controversial figures in our culture. Are we who traffic in the humanities guardians or destroyers of civilization? Are we good? Are we evil? Like the protagonist of the 2008 superhero film The Dark Knight, are we the heroes our culture deserves, but not the ones it needs right now? I feel as close to Batman in this moment as I am likely to get. I am happy and terrified to be here. Let us begin this evening with an excerpt from The Dollmaker, a novel by Harriette Simpson Arnow, published in 1954. The following is an abridged version of a scene between Gertie Nevels—the tall, artistic, mountain woman who is The Dollmaker’s protagonist—and Mrs. Whittle, Nevels’ son Reuben’s homeroom teacher in an overcrowded school in wartime Detroit. Here we go:

From An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United Statesby Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz: “The United States did nothing to halt the flow of squatters into Cherokee territory as the boundary was drawn in the [1791 Treaty of Holston]. A year after the treaty was signed, war broke out, and the Chickamaugas, under the leadership of Dragging Canoe, attacked squatters, even laying siege to Nashville…. The settlers organized an offensive against the Chickamaugas. The federal Indian agent attempted to persuade the Chickamaugas to stop fighting, warning that the frontier settlers were ‘always dreadful, not only to the warriors, but to the innocent and helpless women and children, and old men.’ The agent also warned the settlers against attacking Indigenous towns, but he had to order the militia to disperse a mob of three hundred settlers, who, as he wrote, out of a ‘mistaken zeal to serve their country’ had gathered to destroy ‘as many as they could of the Cherokee towns.’ [John] Sevier and his rangers invaded the Chickamaugas’ towns in September 1793, with a stated mission of total destruction. Although forbidden by the federal agent to attack the villages, Sevier gave orders for a scorched-earth offensive…. In squatter settlements, ruthless leaders like Sevier were not the exception but the rule. Once they had full control and got what they wanted, they made their peace with the federal government, which depended on their actions to expand the republic’s territory. Sevier went on to serve as a US representative from North Carolina and as governor of Tennessee. To this day, such men are idolized as great heroes, embodying the essence of the ‘American spirit.’ A bronze statue of John Sevier in his ranger uniform stands today in the National Statuary Hall of the US Capitol.”  I just finished reading Charles Dodd White’s latest novel How Fire Runs (Ohio UP, 2020) and what a timely read it is. Neo-Nazi white supremacist Gavin Noon sets up in a former mental hospital in a fictional Carter County, Tennessee and attempts to get into local politics after being scolded for leading his cronies in an unauthorized highway cleanup. Noon’s particular brand of evil does not stay banal for long and ruckus ensues. CDW does a great job of dramatizing local politics and reminding the reader that romantic foibles do not abate just because one is involved in making history. How Fire Runs is a page-turner, engages insider-outsider politics and the politics of race in the southern mountains, creates a gallery of well-wrought characters, includes great nature writing, and maintains a lightning pace without abandoning White’s gift for lyricism. How Fire Runs is a good one. I reckon the third novel in the Canard County trilogy is coming out March 2021. It's called POP. I had a bunch of leftover illustrations. I'll post some of them here. Or at least one. Here it is.

The following are quotes copied out of How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective (Haymarket Books, 2017). How We Got Free is a series of interviews conducted and edited by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor with Barbara Smith, Beverly Smith, Demita Frazier, Alicia Garza. The book also contains an essay from Barbara Ransby.

We are a collective of Black feminists who have been meeting together since 1974. During that time we have been involved in the process of defining and clarifying our politics, while at the same time doing political work within our own group and in coalition with other progressive organizations and movements. The most general statement of our politics at the present time would be that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives. As Black women we see Black feminism as the logical political movement to combat the manifold and simultaneous oppressions that all women of color face. –from the Combahee River Collective Statement, 1977 When I think about Black feminism, and I think about what we bring in terms of adding to the synthesis and creation of a new hybrid like socialism—I want to build new structures that help us to get people to feel that socialism is a juicy thing. –Demita Frazier [T]he way affirmative action doctrine is positioned—that all the improvement in our status is based on the idea "that we are ‘evolving’ into better people because of integration,” a result of closer proximity to whiteness—and that this was about us ascending to new levels of competence, when in fact what it has really been about was a very, very, very tiny developmental surge forward on the part of white people, just beginning to confront the illusion of white supremacy. Because our competence has never been a question in my mind. Our brilliance has never been a question. Historically proven, for many, many cultures across millennia. –Demita Frazier For me freedom is getting away from this sick Mammon-driven, nihilistic bullshit we call popular culture. –Demita Frazier Our movements have to be composed of people from across the class spectrum and people who also have power. Right? If we want to compete for power, then part of what it means is we have to amass our power as a unit. And it also means we have to take some of theirs. That’s how you compete, right? You’ve got to break some of their folks and be like, “Which side are you actually on?” Right? And it also means that our vision for what a new society can look like has to appeal to more than just the intellectual class of activists and organizers. –Alicia Garza What brings us together even though we don’t all share the same life? We share the same aspirations. We yearn for the same things. So what does it mean then for us to be in deep and principled relationship with each other? –Alicia Garza [W]e don’t just want a seat at the table. We want the table. We want to decide who is sitting at the table. Right? And then maybe we want to get rid of the table. –Alicia Garza [W]hen you attempt to dismantle a global system and a global organizing principle, there are all kinds of ways in which the state tries to discourage that. –Alicia Garza [W]e’re in that place where we can talk as much shit about how fucked up things are, but when folks don’t know anything else they either don’t participate or they make the wrong choice because it’s safer than not knowing. You know? --Alicia Garza When I think about political power I can’t separate it from electoral organizing. I do separate it from Democrats and Republicans. Electoral organizing is still a vehicle that most people participate in. And if it wasn’t important for Black folks to be in that, they wouldn’t try to take it from us. –Alicia Garza The [Combahee River Collective’s] statement and the practice that surrounded it debunks the notion that so-called identity politics represents a narrowing rather than a broadening of our collective political vision. The document is antiracist, anticapitalist, anti-imperialist, and anti-hetero-patriarchy. That is CRC’s Black feminist agenda. –Barbara Ransby “Every revolutionary is motivated by great feelings of love.” –Che Guevara quoted by Barbara Ransby. |

AuthorRobert Gipe grew up in Kingsport, Tennessee. He lives in Harlan, Kentucky. Archives

April 2022

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed