|

TROUBLESOME 2020

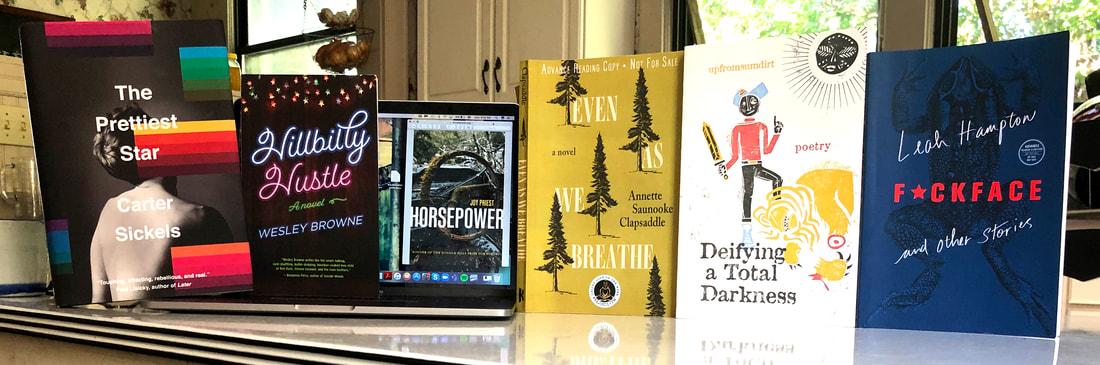

Pandemic, Revolution, and New Books. Books discussed: The Prettiest Star by Carter Sickels (Hub City Books), Horsepower by Joy Priest (University of Pittsburgh Press), Even As We Breathe by Annette Saunooke Clapsaddle (Fireside Industries, University Press of Kentucky), Hillbilly Hustle by Wesley Browne (West Virginia University Press), Deifying A Total Darkness by upfromsumdirt (Harry Tankoos Books), and Fuckface and Other Stories by Leah Hampton (Henry Holt). 1. Ball of Confusion. Breonna Taylor and George Floyd died at the hands of the police this spring--Breonna Taylor shot in her bed in Louisville; George Floyd with an officer’s knee on his neck in Minneapolis. David McAtee was gunned down in the doorway of his Louisville barbecue restaurant by a National Guardsman during the protests against Taylor and Floyd’s deaths. Earlier this year, two white men killed Ahmaud Arbery while he jogged in Glynn County, Georgia. Millions clamor for a better world in their name and the names of thousands of other Black, Indigenous, and People of Color killed unnecessarily in a world sick on racism and addicted to white supremacy. The killings of Taylor, Floyd, McAtee, and Arbery happened in the midst of an international pandemic which has killed over five hundred thousand people. The cumulative weight of all this death has cracked open the world. The blunt trauma of so much unnecessary death has drawn hope’s jaw slack and made visible something better, something else, stuck in hope’s craw. In quarantine, we assemble online and in the streets to reach out for new possibility, but even as we touch it, we wonder: can we hold it? Can we pull it out, set it on its feet, name it, grow it? Fourth of July and fireworks sales are booming. The President is doing photo ops at Mt. Rushmore on land sacred to the Lakota, holding Juneteenth rallies in Tulsa on the site of Black massacre. Children are still in cages on the southern border. Our elderly die COVID-struck, side-by-side with their caretakers. Others, disproportionately black and brown, die because they have to go to work in restaurants and stores, serving people who don’t care enough about their lives to wear a mask. Police behind shields with insignia and nameplates covered beat down peaceful protestors and journalists. Facebook and Twitter are full of hate and lies, full of potshots and our abandonment of one another, a spirit-looting riot all their own. Still we educate each other. We listen. We hold onto love. We bail each other out of jail. We build coalition. We increase and deepen our demands. Where will we find the strength? How will we hold one another on the path? How will we know the path is the path? How do we know love will carry the day? A ball of confusion. That’s what the world is today. It was true in 1970 when the Temptations first sang it. It was true when Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong wrote the song. It is true in 2020. Into this world of pandemic and revolution come six books. Six books written by six friends. For four of them, it is their first book. We want to be excited for one another. We want to celebrate. You take on writing a book, and you are never sure it’s worth the effort. You think perhaps your time might be better spent, on more direct things, because the world is on fire. Then the book is done. It has a pretty cover full of blurbs written by your heroes and friends. People invite you to come read out of it. They promise free tote bags and coffee mugs, nice book-signing pens you don’t have to return when the signing’s over. You get it all lined out and then the COVID hits and it all goes virtual (bookstores shuttered, workshops postponed, festivals cancelled). Your book tour turns into you trying to hide your bad hair on the Zoom. Lord love the Zoom. The Zoom has given us a way to be with one another in these shut-in days, and even if it does feel like ground control to Major Tom most of the time, it has turned us into a massive, nationwide, Brady Bunch opening credits sequence, heads floating in a most peculiar way, smiling and waving, sometimes muted, sometimes not, our circuits not yet dead. As it is hard to know whether writing is what needs doing in these days of pandemic and revolution, it is harder still to know if writing about writing is what needs doing. One grows tired of one’s own voice. But these are my friends. I have seen their hearts. Perhaps a few minutes together. 2. Planet Earth is blue. To evoke Major Tom, the protagonist of David Bowie’s song “Space Oddity,” is a decent way to enter the headspace of Carter Sickels’ new novel, The Prettiest Star. The Prettiest Star is about a young man dying in the 80s of AIDS-related complications, come home from New York to the country, to southeast Ohio, to a family and community that isn’t ready for him to come home. But Brian, the dying man, an ardent Bowie fan, finds the ones ready to love him, and they help a few others get ready to love him. If you were grown in the 80s, it will take you right back to that time of upturned Polo shirt collars, center-parted hair, and deep homophobia. If you weren’t grown in the 80s, you will still find The Prettiest Star a beautiful meditation on courage and cowardice and claiming one’s humanity in the face of prejudice and threat. The Prettiest Star reminds us this isn’t the first time in our history we’ve let politics get the best of good public health practice, and in the process let a lot of good people die for no good reason. Part of Carter’s book launch was supposed to be at Maribeth Tolson’s place, Ole Hookers, a bar on Limestone Street, closer to downtown Lexington than the UK campus. The party was to be in April and feature white wine and tequila shots. We love Ole Hookers. We have been tangled up there many a time. But Ole Hookers got cancelled cause of the COVID. Instead, Carter’s publishers, Hub City Books, set up a Zoom party where people from all over Carter’s life—Portland, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, West Virginia, Kentucky—people from his movie family who worked on the film version of his first novel, The Evening Hour--came together to beam, try and figure out who one another was, and toast Carter each in our own little boxes. It was wonderful in the way of a big wedding, but without the open bar. We do miss bars. Ole Hookers is back open, across the street from Soundbar, the bar where we watched the 2016 election returns with Carter and his partner Jose. That night didn’t go quite like we hoped, and I can’t help but wonder how things might be different now if that night in November of 2016 had gone differently. 3. The Banks of The Ohio. 2020 saw another election that didn’t go differently in Kentucky. A lot of us like Charles Booker, a state rep from Louisville who almost, but not quite, got to run against Mitch McConnell for a seat in the United States Senate this fall. I appreciated the way Booker tried to connect the mountains to the city, tried to point out what all working people have in common. I liked the way he didn’t mind being seen protesting Breonna Taylor and David McAtee’s killing, the way he didn’t mind advocating for a different way to go at public safety. Charles Booker seems like a good man. I hope he isn’t done seeking public office. I hope the demonstrations for racial justice and true public safety aren’t done either. I haven’t gone to Louisville yet this year. I almost did. I had tickets to an event this spring I was looking forward to—the premiere of a documentary called River City Drumbeat. The movie tells the story of artists and community organizers Nardie White and Albert Shumake and the many young artists—including Albert—who grew up safer because of their involvement in the River City Drum Corps. River City Drumbeat is about kids and culture and people taking care of each other. It’s about continuity, and handing off your work to somebody willing and able to take it on. It’s about how good and important art is, how it can order your life, how it can be a stay against chaos. The movie is set in the West End of Louisville, some of the kids attending the same high school as Muhammad Ali, same high school as Joy Priest, a poet we will discuss in a minute. It’s the same part of town where David McAtee cooked barbecue the day he was killed. When the premiere event got cancelled, I watched River City Drumbeat online. I cried and cried it was so good. The name of this essay comes from Troublesome Creek, which is in Knott County and runs through the Hindman Settlement School. A lot of us who write go to Hindman in the summer time, to the Appalachian Writers Workshop. Last year, I met a poet there named Joy Priest. She’s from Louisville. There is a lot of socializing at Hindman. Sitting in the dark after hours, maybe drinking a little, sharing Grippos and Keith Stewart’s salty nuts. During our 2019 Hindman nights, Joy Priest read poems out of a three-ring binder, sitting on the edge of a plastic Adirondack chair in the wee hours. She got us speculating on the cars we might have been conceived in. She is Hindman people. Good to write, good to read, good to sit up late and tell. This spring and summer, Joy has helped me know how to support the uprisings in Louisville, even if I was too chicken to go. We have compared political notes, mostly over the Instagram. Regarding the youth-led Black Lives Matter demonstration in Harlan this spring, Joy said: “I’m glad someone is there to remind Harlan of its coalition history.” Joy told me about a radio station in Louisville she listened to when she was younger, played mostly music by Black artists, had the tagline “From Clarksville to Corbin.” We’d both like to know more about how that tagline came to be. Joy talked about—and this was before it came out in the papers—a possible connection between violence in the West End—and in particular, the death of Breonna Taylor—and gentrification. One of Joy’s poems is called “Ode To My First Car, 1988 Cutlass Supreme Classic 307 V8, Dual Exhaust.” It’s in her forthcoming book, Horsepower. Here’s part of it: & then the scorched pistons Clanking my favorite machine to a stall On the dark parkway, named for a Nation Corralled far from here. 307 horses Giving out, their knees dropping To the winter asphalt, the oil pan run Dry. I’d been trying to escape the limits Of my mother’s vision: 550 feet from Dixie, The red light falling into green, someone’s horn Cursing like a starter pistol. Since I’d known The horses, I’d been running. When the gun Went off, I knew to run. Joy found out she won the Donald Hall Prize for Poetry from AWP for Horsepower while we were at Hindman. Natasha Trethewey was the judge. Trethewey called Joy’s a “restless, resilient spirit,” and her poetry “an urgent grappling with the desire to both remember and outrun the past, with history both personal and communal, and the complexities of American racism in its most intimate manifestation—familial love.” Hindman is a good place to be when something good happens in your writing life. We read Trethewey’s words together, over and over. Joy grew up in the shadow of Churchill Downs. She’s got poems about that and having a white momma and a black daddy, and her grandfather’s nightstick, and what a dick George Zimmerman is. We’ll probably all still be hemmed up due to COVID when Horsepower comes out this fall, and Joy’s moved to Houston to go to grad school, but we’ll be at those virtual readings, remembering, as Gurney Norman taught us, how Troublesome Creek flows into the Kentucky River, which flows into the Ohio, which flows past Louisville on its way to the Mississippi, which flows into the Gulf, which mingles with the bays of Galveston and Trinity and Burnet, on up Buffalo Bayou, to within wifi distance of the University of Houston, in the adopted city of George Floyd and Joy Priest. We will be as together as we can be. We will be together. 4. Sugar So Finicky. Here’s how Cowney Sequoyah, the 19-year-old Cherokee protagonist of Annette Saunooke Clapsaddle’s first novel, Even As We Breathe, remembers the night his grandmother, his Lishie, died: That night in my dreams or otherwise, Lishie asked me if I remembered how to make her pound cake…. Did I remember how finicky sugar was in general? Like when we made Christmas peanut brittle? If you heat it, it burns so easily—hardening into a sticky, bitter brittle. You must always watch sugar closely…. It seemed like a delusional fever dream, piecing repetitive memories together into a moment. Why would Lishie rise from deathbed to share recipes with me? … If that aint love advice, what is? …I only wish I’d recognized it in time to ask her what to do when there was no sugar in the cupboard to spare, when it was rationed in times of war. Annette Saunooke Clapsaddle was also at Hindman this past summer. Her first novel is the story of a young man who grew up on the Qualla Boundary, like Clapsaddle an enrolled member of the Eastern Band of the Cherokee, in western North Carolina. It’s set during World War II when the U.S. government used the Grove Park Inn in Asheville as a prisoner of war camp for international diplomats from Axis countries. The young man, Cowney Sequoyah—tender as spring peas with a “skee-jawed foot” kept him out of the service—goes to work at the Grove Park, falls in love with a woman whose gaze lands elsewhere, gets accused of a kidnapping, deals with racism on multiple fronts, and balances his desire to make money and go to college with his love for his grandmother and his community, if not his sour old Uncle Bud, who wants him to make side money selling black bear gall bladders to imprisoned Japanese diplomats. Clapsaddle’s words have an easy grace, but they work hard, often pulling double-duty. For example, the sugar above is the literal sweetness of candy and cakes, but the passage also seems a meditation on the nature of sweetness, and how easily “being sweet” can betray us, leave us bitter and hard-shelled. This world will burn you in a second, as sweet Cowney learns. Even As We Breathe is shot through with deluxe use of image. At another point, Cowney, feeling stifled and too-known in his small mountain community, says: There are some nights, some days, you just pray it will rain. Not because the crops need it or the wells are low. Sometimes you need the clouds to burst and release the pressure building around you. The smoke, its constant swarm and release with changing winds, smothered the skyline, suffocating me in the process. I wanted it to feel like it did back at the Inn with the rain pouring nearly every day. Many a rural youth knows the feeling of release that comes on arriving into urban anonymity, represented here by the more frequent rain in Asheville. I had the privilege to referee an arm-wrestling contest in which Annette participated this summer at Hindman. And I’ve had the privilege to eat corn meal and grits ground by her father. There is a sweetness in that corn and in Annette’s work that is neither finicky nor too sweet—it is an even sweetness, rich and sustaining, born of loving ground. Even As We Breathe is the first novel on the Fireside Industries imprint of the University Press of Kentucky. Fireside is connected to Hindman Settlement School. Annette and her editor, the estimable Silas House (whose first three novels are also just out in new editions), along with a number of others, were part of a virtual fundraiser for scholarships to Appalachian Writers Workshop just after the COVID sent us all to the house. We have all drawn strength from the community Hindman has allowed us to create, and so the online gatherings were a thing we were glad to do. It was heart-lifting to listen to one another read and talk. There was a giddiness to the comments, greetings, hearts, thumbs-up, and smiley faces bubbling up the screen. The event was organized by the school in collaboration with Wesley Browne, whose own book entered the world this spring only to be swallowed up by the COVID. Wes’s book is called Hillbilly Hustle. 5. Good To Hear Your Voice. When you drive over two hours on a suspended license in a wrecked car through three counties to your possible death, a hell of a lot goes through your mind. Knox drove it pretty slow. –from Hillbilly Hustle. Hillbilly Hustle is a noir. It’s about bad men and marijuana and pizza. And also poker. With considerable tattoo-related material. The author, Wes Browne, is a lawyer in Richmond, Kentucky who owns a pizza joint and has played in the World Series of Poker. He also has a tattoo. So he knows what he’s talking about. But truth be told, Wes isn’t that hard-boiled for a hard-boiled noir writer. In fact, in some ways, he’s kind of a softie, heart big as a battleship. Now that I think about it, hardly anybody gets killed in Hillbilly Hustle. It’s kind of a soft-boiled noir. But I don’t think that’s a problem. Wes’s protagonist is a sad sack named Knox. He owns a pizza parlor and wears shorts and shower slides all winter and only makes good decisions when he’s sitting at a poker table. Knox has the misfortune to win a bunch of money in a poker game from a notorious outlaw who runs things in a fictionalized version of Jackson County, Kentucky. Knox ends up indebted to the notorious outlaw, whose name is Burl Spoon, and has to sell pot for him. He ends up deep in debt to Burl and in trouble way over his head with everybody else. He’s pitiful. If he were a horse, you’d shoot him. But he’s a protagonist, so you hang in there. Knox and Burl are both independent businessmen, operating outside the mainstream corporate capital channels. They are largely on their own, and Wes’s book is a celebration of the hustle, especially as it plays out among small-time operators. There is a sweetness of tone that contrasts with the genuine sense of menace Wes gins up around Burl and his burly thug, The Greek. Nowhere is that menace more terrifying than when Knox calls his parents, whom he has been supporting financially, just to hear their voices, at a time when he is pretty sure he is driving to his doom at the hands of Burl and The Greek. Knox fears his parents are going to get killed, too, but he keeps his upper lip stiff as his dad chatters on about the UK ball team, and his mom asks “How’s the pizza business? Is it picking up at all?” “A little bit,” [Knox] lied to her. “Well, that’s good,” she said. “Maybe the holidays will be busy.” Knox neared his exit. “Maybe. I sure hope so. I guess I should get off here.” “Okay, hon,” his mom said. “Good to hear your voice,” his dad said. “Yours, too,” Knox said. “I love you guys.” “Love you, Knox,” they both said, out of unison. Knox used his forearm to wipe his eyes after he hung up. He didn’t want to be alone, but that was all he could take of his parents without coming apart. My fear for Knox’s parents was very real when I read that. One hates to mix one’s family up in one’s idiocy, and Wes does a fine job of making Knox’s idiocy ours, and thus his regret land in our stomachs. Wes put together a couple of face-to-face events for Hillbilly Hustle before the COVID kicked in. He had a Hillbilly Hustlebeer tie-in with a local brewery in Georgetown and Lexington. Wes also hosts a reading series called Pages & Pints at Apollo Pizza, his family’s pizza joint and taproom in Richmond. Wes is quite the impresario, and a wonderful promoter and supporter of the literary scene in Kentucky. With this spring’s Hindman fundraisers, he even made Zoom fun. Of course, the one I did was with some of the more enjoyable people to spend time with in the whole literary scene--Crystal Wilkinson, author of The Birds of Opulence (among other works), and upfromsumdirt, the author of the next book under discussion. 6. Viva sumdirt. folks anguish over art depicting happy slaves or confederate generals, but white skin itself is the mural of oppression that i must navigate around every single day. this isnt a condemnation. it's a fact of historical context between our races. white people see black skin and fear for their imagined virtues... black people see white skin and see a perpetual apocalypse. when in america has whiteness never represented a dystopian wasteland for black people? if we've found any happiness, it's not in our circumstances...it's in what we shelter from the white gaze. —@upfromsumdirt, Twitter, July 8, 2020 Upfromsumdirt grew up in Louisville and lives in Lexington. With his partner Crystal Wilkinson, in the guise of his alter ego Ronald Davis, he ran The Wild Fig bookstore on Leestown Road and then on North Lime in Lexington. He is a visual artist and designer of books, book covers, and all manner of posters and flyers. Upfromsumdirt’s poetry is collected in the new volume from Harry Tankoos Books entitled Deifying A Total Darkness. Reading Deifying A Total Darknessis a spaceship ride (with comic books and vintage TV Guides in the glove box and interplanetary pit stops at Frank’s Donuts and Ollie’s Trolley) through the African diaspora, a cosmos of dirt farms, “ransom notes written in crayon and sausage gravy,” “living tongues made into limestone when/ villains flooded the valley,” “Cul-de-Sac Safari[s],” and even the occasional “redemptively engrossing storybook love.” From time to time, dirt will remind us how he is not academe, is not part of the poetry-industrial complex: Then again, it’s not like I was born for recognition, having my mug on mugs, having “viva sumdirt!” silkscreened on t-shirts in every coffee house on an HBCU campus; brothadirt: the lone dissociative black poet always looking in at the MFA chitlin circuit after-party at AWP. (from “Protoplasmic Phrenology”) But his work is a dense skein of reference, running up and down the registers of knowing, high level play. In “Jean Rabin Gives Africa The Bird,” dirt calls out John James Audubon (born Jean Rabin in Santo Domingo to a trader father and a chambermaid mother named Jeanne Rabin who died four months after the boy’s birth) saying Dear Jean, your tale’s an epitome survival of the fittest—1-part Harry Houdini, 1-part Bundini Brown; you escape artist joie de vivre prototype for Colonel Sanders—11 herbs and 4 michelin stars instilled in every sketch, pigments that literally threw you away from your origins, every thin line escaping Haiti and the money- brokers set to deny your inheritance; a favored son adopted by Kentucky and France, you do so love being everything but what you are: the illegitimate love-child of a chambermaid and her plantation-owning pirate – not that I’m judging! who would choose sugar cane over Eiffel Towers? you’re not the first nor the last to sugarcoat a nativity scene. but still you do love New Orleans, claiming the Queen’s City as your place of birth the only place on God’s Green Earth where you found (under the auspices of debauchery) revelry for your darker strokes. but Bacchus was never a patron saint of Haiti. Baron Samedi is your crown. Brother Eshu Elegbra guards your gates and escape routes. The poem concludes: …in Africa concentric circles also have their own secret societies; you, Mr. Frontier-Ornithologist, would fit right in as there’s a role for scarecrows in all the various artforms of Santeria. you see you’ve misconstrued the venerable beliefs of your father’s favorite lover to be the vulgarities of your father’s wife – again not a judgment – but Darwin also believed in dodos and if not in the phoenix then most certainly in its metaphor; in the egg of your soul, John, Jeanne Rabin too takes flight; draw that. Two thoughts on this poem: 1) Wikipedia should underwrite dirt’s work. His is a poetry to be read with one’s mind and browser open. 2) This is some slick poetic swordplay: all thrust and parry, lunge and dodge. It cuts but then slips away, as if the poet’s mind were Forest Whitaker’s blade in the movie Ghost Dog. The verse makes of intellectual flight a homecoming, delivers the treasure chest of culture to the cookout, an act of righteous piracy, stealing back reference and birthright and bringing it to the block party. Dirt’s work is full of head slaps (“Bysshe, Please,” “Anansi With The Laughing Face”) and homing pigeons (“Pell Grant For A Space Force,” “Crissy From the Creek”), “poems that resonate with my daddy’s gruff guffaws and mama’s/ hymnal hum;” and though I fear I will regret it if he ever gets wind of me saying it, I will say it: upfromsumdirt, in backing up his gutpunches and stab wounds with self-deprecation and near-inscrutable allusion, in his setting up poetic shop on the margins, claiming his audience is kindred, but then also speaking truth squarely to a power that wishes him mostly ill, reminds me of that Dickinson woman, the one whose work was nearly lost, the one who posted up in a feminist fortress and brought the ruckus, whose lines are still kicking ass today for anyone willing to offer up ass for the kicking. i cram as many words into a poem as the page can hold. but it's not because i like large file poems... it's because i have a couple hundred years of the Black Voice not mattering as artform to make up for and god only knows when i'll have this chance again. --@upfromsumdirt, Twitter, June 27, 2020 7. Poor Little Bee. Poor World. Like upfromsumdirt, my friend Leah Hampton is also good to Tweet. The title of this section comes from one of my favorites of hers: “A big ol' buzzy fuzzy bee flew in the house today and died so we put his body outside in the dogwood's branches and friends, I am so sad. Poor little bee. Poor world.” Leah Hampton lives in western North Carolina, not far from Clyde. Her debut collection, Fuckface and Other Stories, is just out from Henry Holt. These are the stories of Fuckface: “Fuckface,” which concerns itself with dead bears and the unfortunate necessity of Asheville; “Boomer,” which concerns itself with squirrels, forest fire, and the fragility of marriage; “Parkway,” which concerns itself with the accumulation of dead bodies on public land and the inner lives of those charged with their removal; “Devil,” which concerns itself with the toll of violent parenting and the benefits of being able to see things coming; “Meat,” which concerns itself with surviving a fire in a hog barn and the funerals of those good to children; “Frogs,” which concerns itself with how arrogance, the wrong shoes, and people from off can ruin a perfectly dark night for oneself and a string of unborn frogs; “Sparkle,” which concerns itself with the cluelessness of men and the limits of Dolly Parton’s power; “Saint,” which concerns itself with the reconstruction of our experience of the departed and the possibilities of second person narration; “Queen,” which concerns itself with the wages of growing up untrusted and the life and death of beehives; “Wireless,” which concerns itself with the utter sorriness of men and the risks of high school during and after one’s attendance; “Twitchell,” which concerns itself with the cost of industrial prosperity and the mendacity of certain potters; and “Mingo,” which concerns itself the trials of having in-laws and the challenges of male corporeality. A woman named Tina narrates “Mingo.” She’s from southern West Virginia. Her husband’s family is from Harlan County, Kentucky, but has moved away—to Charleston, West Virginia in her husband Howard’s case and Lexington, Kentucky in her sister-in-law Violet’s case. They are reunited by Tina’s father-in-law’s fourth car wreck in as many months. Tina expresses her concern about the father-in-law continuing to drive: I kicked off so much about Hassel being a public threat that Howard’s sister wouldn’t talk to me anymore, either. Not after she told me she wouldn’t let her youngest ride in the car with her own father anymore. I’d already had enough of Violet, with her organic garden and her high shoulders, always acting like I was a superstition she no longer believed. Tina has had several miscarriages. She is also grieving the loss of her childhood home to strip mining. Her husband is pouring the concrete for a useless airport on a strip job near where she grew up. Violet, the sister-in-law, rationalizes her father’s continued driving: “We have to love him through this, you know? It’s so difficult, I think, to lose one’s autonomy. It’s all he has left.” Tina responds: I crinkled my nose and nodded how the pretty girls in middle school used to when they picked on the kids from over my way. I learned her kind’s code a long time ago, and I used it on her now. She knew why…. Violet knew what it meant to hold tight to her child right in front of me. She went quiet. Now she doesn’t talk to me, and Howard shuts down when I say Hassel Fields is a danger. No matter; I hadn’t gone on the last few weekend visits to Lexington anyhow. I’d been busy lately hollowing out. As happens in many of Leah’s stories, the bodies of her characters echo the goings on in the ecosystems around them, in a kind of reverse anthropomorphism. Also, as is typical in this collection, a character, in this case Tina, loves in a way that gets them in trouble with those they love. There is a quality of voice in “Mingo” that threads through these stories. Tina, like many of Leah’s characters, transmit the full volume of their hurt, but in a voice radiating confidence—maybe not confidence they will prevail, but confidence in their own accuracy, confidence that precision in the telling is the best available salve. I don’t know how you will feel about it when you read them, but I felt like Leah’s characters are pretty much justified in their confidence. There is nothing more comforting than people feeling comfortable telling you their problems—particularly when the people feel as real as Leah’s characters do. 8. The Screams Inside Our Hearts. “The outcome [of Hillbilly Hustle] amounts to two things: ‘You can break the rules if you have enough power and money to get away with it,” and “Evil prospers while good just gets by.” I guess either way, it does feel a bit like the way of things right now. The moral arc is supposed to bend toward justice though, right?” –Wes Browne. “Your welfare aint on that rich man’s mind.” –Hazel Dickens. “While the rich and mighty capitalist/ Goes dressed in jewels and silk,/ My darling blue-eyed baby/ Has died for want of milk.” –Sarah Ogan Gunning. Black lives matter. Why has it been so hard for so many white people to find solidarity with those saying Black lives matter? To say it, to believe it, to laugh and cry and reflect on the richness of Black life as revealed in the poetry of upfromsumdirt and Joy Priest, for example, does not diminish one’s ability to laugh and cry and reflect on Indigenous life as described by Clapsaddle, or white life as described by Browne, Hampton, and Sickels. I don’t know why it has been so hard for some. But in thinking about it, I arrived at this: Here in the coalfields, the message handed down through history, through the slaughter of indigenous people; slaughter of the enslaved; slaughter of the coal mines, slaughter in the log woods, slaughter building the railroads; slaughter of the battlefield; slaughter of the strikes and violent opposition to union organizing; slaughter of endless bloody car wrecks in too-sharp curves, broken bodies hauled to shorthanded hospitals; slaughter of pellagra, bloody flux, scurvy, rickets, diabetes, emphysema, pneumoconiosis, silicosis, cardiac arrest, alcoholism; slaughter of OxyContin, Percocet, Lortab, Xanax, Suboxone; slaughter of layoffs, floods, evictions, housefires, forest fires, meth lab fires, coal mine fires, methane explosions, roof falls, and cave-ins; slaughter born of crooked elections, chaotic classrooms, crooked courthouses—the message handed down through all that slaughter is: no lives matter. Which, while true, is not entirely true. Our lives matter to those who love us. For those who believe, our lives matter to Jesus, or to whomever we profess our faith. We have family and friends, doctors and nurses, teachers and social workers, and even, on occasion, certain individuals in law enforcement, to whom our lives matter. But to those at the top, call them what you will—the one-percent, the super-wealthy, the political ruling class, that select group that have seen their wealth and power transmitted from generation to generation, since this country’s beginnings, regardless of the political party in power, that select group that has sent the rest of us to war, has suppressed our wages to increase their profits, have marketed drugs they knew would kill us and called it medicine, have enslaved, imprisoned, and exterminated us, have rationed health care and thereby killed us, all to enrich themselves—it is difficult to make the case that any of our lives matter to this class of people, except as we are needed as labor, or as a market for goods and services, or to fight their wars, or to vote, or to be pitted against one another as a way of distracting us from the way we are being used, the way we are denied our humanity. And pitted against each other we have surely been. Racism, homophobia, sexism, patriarchy—these are not natural things. They are manmade things. They are things that have made, are making, somebody money. Of course, it is our fault when we succumb to them, but it is difficult to see the most financially powerful dismantling these systemic social plagues. If these plagues are to be vanquished, I do not look to the wealthy to do it. We are trained to believe that to “win,” or even to hold what we have, someone has to lose. We have been trained to think that if there are losers, it would be easier on us, on our consciences, if we adopt and hold fiercely the belief that the losers deserve to lose, that the losers are immoral or illegal or inferior. This is what we are taught by people who have no intention of ever letting us win. This is a part of how we become the agents of one another’s slaughter. But many, if not most of us, despite all the competition and survival-of-the-fittest jive bred into us, are not primarily concerned with winning. We are primarily concerned with the health, safety, and happiness of ourselves and our loved ones. We are primarily concerned with the ability to go to the doctor when we are sick, to have food and shelter and good work at a fair rate of pay, the ability to take time off to enjoy ourselves and be good friends and/or family members. And if the pandemic has taught us anything, it is that being in community is important to us, that we matter to one another, that we miss one another when we are not able to be together. 9. The Vastness Of The One. just my monthly call for a matriarchal government. —@upfromsumdirt, Twitter, July 2, 2020 We must be able to experience each death as an individually painful and unique loss. Perhaps we are numbed to inaction by the thousands of losses precisely because we have never truly appreciated the vastness of the one. —AIDS activist Michael Callen, quoted by Belinda Mason in the Appalshop film, Belinda Mama, I can’t breathe. —George Floyd. In Carter Sickels’ The Prettiest Star, one of the strongest characters is Andrew, a gay man who stays in rural southeast Ohio, works at Sears, and comes to be one of the primary caretakers of Brian, the local man who moved to New York, came out there, and comes home to die from complications related to AIDS. Brian’s homophobic mom Sharon, who has very reluctantly taken up the work of comforting her son, has this to say about Andrew: “At first I just wanted Andrew to leave us alone. His flowery cologne and silky, bright shirts, his fluttering hands, overly expressive eyes—he’s the type you can take one look at and know.” Sharon tells Andrew, as he is washing dishes for Brian, “You don’t have to do this,” and then, as Sharon narrates: Andrew neatly folds the towel and drapes it over the counter. “Yes, I do. I have to, and so do you. It’s the only option.” He looks at me, serious and clear-eyed. “This is the only thing we have to do. Take care of him.” In Even As We Breathe, Cowney’s grandmother tells him to walk home after church, that she is staying, that “Myrtle’s boy can bring me back after.” Cowney gives her the keys to their car because “what Lishie didn’t have to say was that Myrtle’s boy didn’t have a car of his own, nor did any member of their family, so he would be driving ours. This was how she could disguise her favor for his.” Cowney says Lishie “could go to great lengths to ensure that no one publicly recognized her for kindness, fearful that it might insinuate weakness, gentleness, or naivete. She couldn’t afford such labels. None of us could.” Not long ago, The Ringer published a story about Breonna Taylor’s family and how they are dealing with her murder. In the piece, Taylor’s mother, Tamika Palmer, speaks about her introversion and reluctance to enter the spotlight as her daughter’s murder triggered international protests and calls for defunding of the police and protections for the lives of Black, Indigenous, and people of color. The story follows Palmer and her family to a protest and celebration of Breonna Taylor in downtown Louisville on the day before what would have been her twenty-seventh birthday. Of the event, which was attended by thousands of people and filled the streets of several city blocks, Palmer says, “It was overwhelming, but it’s beautiful. I’ve never seen anything like that in my life. All I kept saying was, ‘Look at this love.’” Palmer goes on to say, “I felt like I was a part of some movement, that it wasn’t about me and Breonna. It was about a bigger cause, a bigger thing. I was just like, ‘Look at the world change.’” Can love lead to change? How do we as a society love our way into a brighter future? In the wake of the killing of “Susie Jackson, Ethel Lance, Clementa Pinckney, Tywanza Sanders, Cynthia Hurd, Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, Depyane Middleton Doctor, Daniel Simmons and Myra Thompson in a black Charleston church by a cowardly white American thug,” Kiese Laymon wrote: “Love reckons with the past and evil reminds us to look to the future. Evil loves tomorrow because peddling in possibility is what abusers do.” As someone who has caused harm, I can vouch for the truth of Laymon’s statement. I have promised to do better many times. And I have come to understand how operating from a place of love—not fear, not insecurity, not an inherited idea of what a man should be—has led to fewer promises on my part, more centering of others in my thinking and feeling, a clearer sense of what it means to act lovingly in the present, and an openness to the notion that reckoning—the settling of accounts, the calculating of effects—sets myself and others on a journey towards a more genuine freedom. Andrew in The Prettiest Star, Lishie in Even As We Breathe, the voice in the poetry and prose of Joy Priest, upfromsumdirt, Wesley Browne, and Leah Hampton, as well as Tamika Palmer, Kiese Laymon, and many of the others mentioned in this essay, embody the vulnerability of navigating by the lights of love, looking backward to move forward. There is a reason those that prosper in the world as it is belittle the study of history and the reading of literature. The prosperous understand the threat inherent in reflection. “Pegasus” is the final poem in Joy Priest’s Horsepower. It goes like this: Before I leave for good I lift the pie server a final time Drop the receipt facedown Next to the lemon blueberry slice Then my apron in the parking lot Like a betting ticket. There A horse greets me. But I see it’s only a Gallopalooza, stationary As all the others scattered Across the city. I move on. Can’t go home So I disrobe in a stranger’s yard Wash the batter away with a garden hose Then ride the night buses Like a carousel. Static girl. Moving room Of mirrors. Stilled blue bolts Streaking the dark—There & then not. A stream of atoms being pulled From my cheek. I’m splitting. I’m coming apart. I’m leaving & being left. Looking for you In all your haunts. Until I realize I will find you At one of my own: In the long field Synced lightning bugs near Their show’s climax. In the brief flashes Of cold light, a glimpse Of your coat. Black as flight. When they move on, it’s just us Six legs to the ground, still as statues Touching flat the bridge of our noses. When you release your wings They swing wide as a gate & the air lifts the snakes from my shoulders. In Greek mythology, as I understand it, Pegasus is a winged horse. Pegasus’ momma is Medusa. His daddy is Poseidon. Poseidon rapes Medusa to sire Pegasus. Because Poseidon raped Medusa in Athena’s temple, Athena turns Medusa’s hair into snakes and makes it so anyone who looks at Medusa’s face turns to stone. Perseus cuts off Medusa’s head and Pegasus springs from her neck. Perseus then uses Medusa’s severed head to turn a bunch of other sword-wagging manly men into stone and Pegasus grows up to enable other hubris-breathing, scary female slaughtering hero types. If you’re Medusa, it seems to me, this is some bullshit. You got Athena enabling Poseidon’s rapy ways and punishing you with a snake hair and a face that turns people to stone. You got Perseus beheading you for no good reason (If you don’t want to turn to stone, Perseus, don’t look at her. Nobody gave you permission to look at her, Perseus). Small wonder Medusa has become a feminist icon, the embodiment of righteous female anger in the face of a jacked-up patriarchal process for dealing with women who scare men that continues largely unimpeded to this day. Enter Joy Priest. Her Medusa works in a restaurant serving pie. She quits, shucks off her clothes, rides the bus naked, follows thunder and lightning, which turns to cold silent lightning bugs, until she finds her lost boy, Pegasus, who is usually depicted as white, but is now “Black as Flight.” The lightning bugs withdraw, Pegasus and Medusa bump noses, and he spreads his wings and lifts the snakes from her shoulders. Least that’s the way I read it, and I would have to say that if that’s what is happening, it is some pretty bad ass reckoning with the past. Greek mythology is straight up belly of the beast Western Civ white supremacy ground zero. And Joy flips it. Sets the tale in Louisville. Makes it a Black and working class story. Makes it tender and bloodless. There’s no macho heroism. Pegasus does not destroy his mother’s snakes. Or pull some divine intervention. Or call down some capricious god. He flaps his wings and lifts the snakes from her shoulders. Lifts the anger, mendacity, pettiness, poison, fear, terror the snakes represent from his mother’s shoulders. The moment of mutual aid between mother and son does not include flight, much less escape. Just air, relief. For Pegasus to lift the snakes off her shoulders is enough for Priest to complete the poem. By withholding the snake hair till the last couplet, Priest gives the poem’s conclusion an electric jolt, a shock of recognition. A white horse turned Black. A gorgon turned waitress. Mother and son reunite and transcend the bullshit of Western civilization in a single loving gesture. Neither are freed. But both are seen. Felt. The vastness of one working mother, the love of one lost Black child.

Berea College will be the scene of a giant gathering of Appalachian writers talking publicly with one another, reading out loud, and hanging out. bell hooks, Denise Giardina, Frank X Walker, Darnell Arnoult, and a gang of others will be there. The Berea Appalachian Symposium promises to be a landmark in the discussion of Appalachian Lit. I'm doing a thing with Amy Greene, Charles Dodd White, and Glenn Taylor about writing in the 21st century on Thursday September 10 at 9:45 with a book signing to follow. Thank Silas House for putting this together. Come see it. The whole dang thing is free as a bird. Full schedule here.

Thanks to the good folks at Union Avenue Books in Knoxville, Tennessee, I will be reading with two of my favorite poets, Denton Loving and Jesse Graves, on Sunday September 13th at 3pm. It will be good to be in East Tennessee with two such erstwhile East Tennesseeans. Come join us.

Thanks to Jayne Moore Waldrop for mentioning Trampoline in her survey of recent books by Kentuckians. Also mentioned: Nickole Brown, Riley Hanick, Emily Bingham, Wendell Berry, and Amanda Driscoll.

American sweetheart Glenn Taylor has got a roundup of Appalachian books over on the snazzy literary blog Electric Literature that mentions Trampoline in the same digital breath as works by Ann Pancake, George Singleton, Frank X Walker, Crystal Wilkinson, and Dot Jackson. Flip em, trade em, collect em all. And read em. And read Glenn's new novel A Hanging at Cinder Bottom while you're at it.

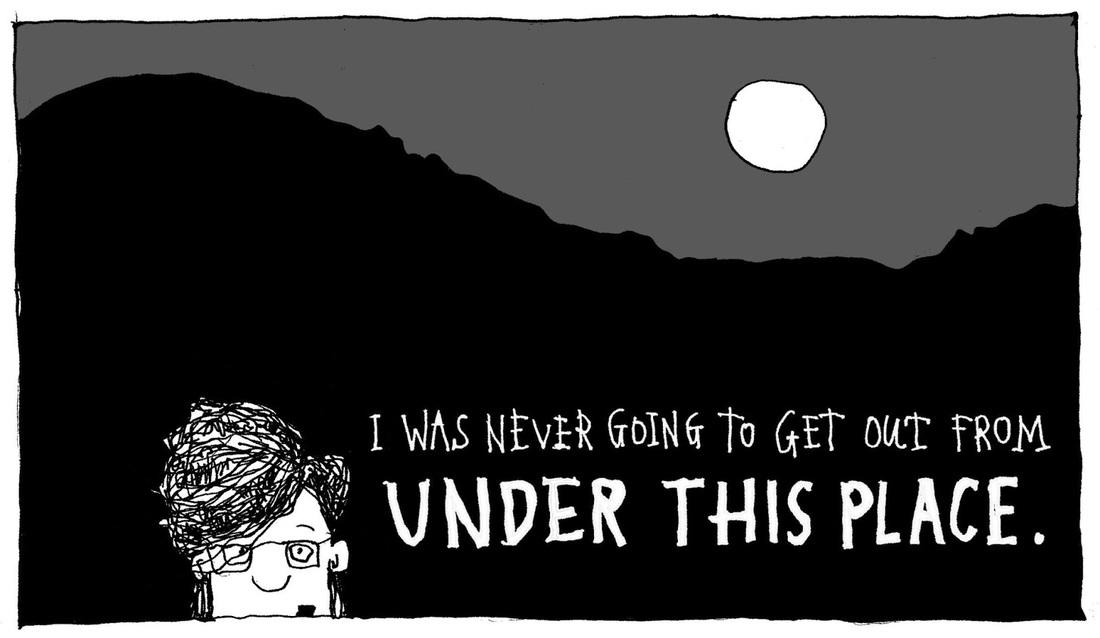

Thanks, Sheldon Lee Compton, for the mention on the dang slick blog, Bent Country.

|

AuthorRobert Gipe grew up in Kingsport, Tennessee. He lives in Harlan, Kentucky. Archives

April 2022

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed